- Home

- John Boyne

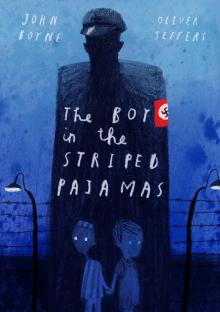

The Boy In The Striped Pyjamas

The Boy In The Striped Pyjamas Read online

The Boy In The Striped Pyjamas

John Boyne

Berlin 1942 – when Bruno returns home from school one day, he discovers that his belongings are being packed in crates. His father has received a promotion and the family must move from their home to a new house far far away, where there is no one to play with and nothing to do. A tall fence running alongside stretches as far as the eye can see and cuts him off from the strange people he can see in the distance. But Bruno longs to be an explorer and decides that there must be more to this desolate new place than meets the eye. While exploring his new environment, he meets another boy whose life and circumstances are very different to his own, and their meeting results in a friendship that has devastating consequences.

John Boyne

The Boy In The Striped Pyjamas

© 2006

For Jamie Lynch

Acknowledgements

For all their advice and insightful comments and for never allowing me to lose my focus on the story, many thanks to David Fickling, Bella Pearson and Linda Sargent. And for getting behind this from the start- thanks, as ever, to my agent Simon Trewin.

Thanks also to my old friend Janette Jenkins for her great encouragement after reading an early draft.

Chapter One

Bruno Makes a Discovery

One afternoon, when Bruno came home from school, he was surprised to find Maria, the family's maid-who always kept her head bowed and never looked up from the carpet-standing in his bedroom, pulling all his belongings out of the wardrobe and packing them in four large wooden crates, even the things he'd hidden at the back that belonged to him and were nobody else's business.

'What are you doing?' he asked in as polite a tone as he could muster, for although he wasn't happy to come home and find someone going through his possessions, his mother had always told him that he was to treat Maria respectfully and not just imitate the Way Father spoke to her. 'You take your hands off my things.'

Maria shook her head and pointed towards the staircase behind him, where Bruno's mother had just appeared. She was a tall woman with long red hair that she bundled into a sort of net behind her head, and she was twisting her hands together nervously as if there was something she didn't want to have to say or something she didn't want to have to believe.

'Mother,' said Bruno, marching towards her, 'what's going on? Why is Maria going through my things?'

'She's packing them,' explained Mother.

'Packing them?' he asked, running quickly through the events of the previous few days to consider whether he'd been particularly naughty or had used those words out loud that he wasn't allowed to use and was being sent away because of it. He couldn't think of anything though. In fact over the last few days he had behaved in a perfectly decent manner to everyone and couldn't remember causing any chaos at all. 'Why?' he asked then. 'What have I done?'

Mother had walked into her own bedroom by then but Lars, the butler, was in there, packing her things too. She sighed and threw her hands in the air in frustration before marching back to the staircase, followed by Bruno, who wasn't going to let the matter drop without an explanation.

'Mother,' he insisted. 'What's going on? Are we moving?'

'Come downstairs with me,' said Mother, leading the way towards the large dining room where the Fury had been to dinner the week before. 'We'll talk down there.'

Bruno ran downstairs and even passed her out on the staircase so that he was waiting in the dining room when she arrived. He looked at her without saying anything for a moment and thought to himself that she couldn't have applied her make-up correctly that morning because the rims of her eyes were more red than usual, like his own after he'd been causing chaos and got into trouble and ended up crying.

'Now, you don't have to worry, Bruno,' said Mother, sitting down in the chair where the beautiful blonde woman who had come to dinner with the Fury had sat and waved at him when Father closed the doors. 'In fact if anything it's going to be a great adventure.'

'What is?' he asked. 'Am I being sent away?'

'No, not just you,' she said, looking as if she might smile for a moment but thinking better of it. 'We all are. Your father and I, Gretel and you. All four of us.'

Bruno thought about this and frowned. He wasn't particularly bothered if Gretel was being sent away because she was a Hopeless Case and caused nothing but trouble for him. But it seemed a little unfair that they all had to go with her.

'But where?' he asked. 'Where are we going exactly? Why can't we stay here?'

'Your father's job,' explained Mother. 'You know how important it is, don't you?'

'Yes, of course,' said Bruno, nodding his head, because there were always so many visitors to the house-men in fantastic uniforms, women with typewriters that he had to keep his mucky hands off-and they were always very polite to Father and told each other that he was a man to watch and that the Fury had big things in mind for him.

'Well, sometimes when someone is very important,' continued Mother, 'the man who employs him asks him to go somewhere else because there's a very special job that needs doing there.'

'What kind of job?' asked Bruno, because if he was honest with himself-which he always tried to be-he wasn't entirely sure what job Father did.

In school they had talked about their fathers one day and Karl had said that his father was a greengrocer, which Bruno knew to be true because he ran the greengrocer's shop in the centre of town. And Daniel had said that his father was a teacher, which Bruno knew to be true because he taught the big boys who it was always wise to steer clear of. And Martin had said that his father was a chef, which Bruno knew to be true because he sometimes collected Martin from school and when he did he always wore a white smock and a tartan apron, as if he'd just stepped out of his kitchen.

But when they asked Bruno what his father did he opened his mouth to tell them, then realized that he didn't know himself. All he could say was that his father was a man to watch and that the Fury had big things in mind for him. Oh, and that he had a fantastic uniform too.

'It's a very important job,' said Mother, hesitating for a moment. 'A job that needs a very special man to do it. You can understand that, can't you?'

'And we all have to go too?' asked Bruno.

'Of course we do,' said Mother. 'You wouldn't want Father to go to his new job on his own and be lonely there, would you?'

'I suppose not,' said Bruno.

'Father would miss us all terribly if we weren't with him,' she added.

'Who would he miss the most?' asked Bruno. 'Me or Gretel?'

'He would miss you both equally,' said Mother, for she was a great believer in not playing favourites, which Bruno respected, especially since he knew that he was her favourite really.

'But what about our house?' asked Bruno. 'Who's going to take care of it while we're gone?'

Mother sighed and looked around the room as if she might never see it again. It was a very beautiful house and had five floors in total, if you included the basement, where Cook made all the food and Maria and Lars sat at the table arguing with each other and calling each other names that you weren't supposed to use. And if you added in the little room at the top of the house with the slanted windows where Bruno could see right across Berlin if he stood up on his tiptoes and held onto the frame tightly.

'We have to close up the house for now,' said Mother. 'But we'll come back to it someday.'

'And what about Cook?' asked Bruno. 'And Lars? And Maria? Are they not going to live in it?'

'They're coming with us,' explained Mother. 'But that's enough questions for now. Maybe you should go upstairs and help Maria with your packing.'

Bruno stood up from the sea

t but didn't go anywhere. There were just a few more questions he needed to put to her before he could allow the matter to be settled.

'And how far away is it?' he asked. 'The new job, I mean. Is it further than a mile away?'

'Oh my,' said Mother with a laugh, although it was a strange kind of laugh because she didn't look happy and turned away from Bruno as if she didn't want him to see her face. 'Yes, Bruno,' she said. 'It's more than a mile away. Quite a lot more than that, in fact.'

Bruno's eyes opened wide and his mouth made the shape of an O. He felt his arms stretching out at his sides like they did whenever something surprised him. 'You don't mean we're leaving Berlin?' he asked, gasping for air as he got the words out.

'I'm afraid so,' said Mother, nodding her head sadly. 'Your father's job is-'

'But what about school?' said Bruno, interrupting her, a thing he knew he was not supposed to do but which he felt he would be forgiven for on this occasion. 'And what about Karl and Daniel and Martin? How will they know where I am when we want to do things together?'

'You'll have to say goodbye to your friends for the time being,' said Mother. 'Although I'm sure you'll see them again in time. And don't interrupt your mother when she's talking, please,' she added, for although this was strange and unpleasant news, there was certainly no need for Bruno to break the rules of politeness which he had been taught.

'Say goodbye to them?' he asked, staring at her in surprise. 'Say goodbye to them?' he repeated, spluttering out the words as if his mouth was full of biscuits that he'd munched into tiny pieces but not actually swallowed yet. 'Say goodbye to Karl and Daniel and Martin?' he continued, his voice coming dangerously close to shouting, which, was not allowed indoors. 'But they're my three best friends for life!'

'Oh, you'll make other friends,' said Mother, waving her hand in the air dismissively, as if the making of a boy's three best friends for life was an easy thing.

'But we had plans,' he protested.

'Plans?' asked Mother, raising an eyebrow. 'What sort of plans?'

'Well, that would be telling,' said Bruno, who could not reveal the exact nature of the plans-which included causing a lot of chaos, especially in a few weeks' time when school finished for the summer holidays and they didn't have to spend all their time just making plans but could actually put them into effect instead.

'I'm sorry, Bruno,' said Mother, 'but your plans are just going to have to wait. We don't have a choice in this.'

'But, Mother!'

'Bruno, that's enough,' she said, snapping at him now and standing up to show him that she was serious when she said that was enough. 'Honestly, only last week you were complaining about how much things have changed here recently'

'Well, I don't like the way we have to turn all the lights off at night now,' he admitted.

'Everyone has to do that,' said Mother. 'It keeps us safe. And who knows, maybe we'll be in less danger if we move away. Now, I need you to go upstairs and help Maria with your packing. We don't have as much time to prepare as I would have liked, thanks to some people.'

Bruno nodded and walked away sadly, knowing that 'some people' was a grown-up's word for 'Father' and one that he wasn't supposed to use himself.

He made his way up the stairs slowly, holding onto the banister with one hand, and wondered whether the new house in the new place where the new job was would have as fine a banister to slide down as this one did. For the banister in this house stretched from the very top floor-just outside the little room where, if he stood on his tiptoes and held onto the frame of the window tightly, he could see right across Berlin-to the ground floor, just in front of the two enormous oak doors. And Bruno liked nothing better than to get on board the banister at the top floor and slide his way through the house, making whooshing sounds as he went.

Down from the top floor to the next one, where Mother and Father's room was, and the large bathroom, and where he wasn't supposed to be in any case.

Down to the next floor, where his own room was, and Gretel's room too, and the smaller bathroom which he was supposed to use more often than he really did.

Down to the ground floor, where you fell off the end of the banister and had to land flat on your two feet or it was five points against you and you had to start all over again.

The banister was the best thing about this house-that and the fact that Grandfather and Grandmother lived so near by-and when he thought about that it made him wonder whether they were coming to the new job too and he presumed that they were because they could hardly be left behind. No one needed Gretel much because she was a Hopeless Case-it would be a lot easier if she stayed to look after the house-but Grandfather and Grandmother? Well, that was an entirely different matter.

Bruno went up the stairs slowly towards his room, but before going inside he looked back down towards the ground floor and saw Mother entering Father's office, which faced the dining room-and was Out Of Bounds At All Times And No Exceptions-and he heard her speaking loudly to him until Father spoke louder than Mother could and that put a stop to their conversation. Then the door of the office closed and Bruno couldn't hear any more so he thought it would be a good idea if he went back to his room and took over the packing from Maria, because otherwise she might pull all his belongings out of the wardrobe without any care or consideration, even the things he'd hidden at the back that belonged to him and were nobody else's business.

Chapter Two

The New House

When he first saw their new house Bruno's eyes opened wide, his mouth made the shape of an O and his arms stretched out at his sides once again. Everything about it seemed to be the exact opposite of their old home and he couldn't believe that they were really going to live there.

The house in Berlin had stood on a quiet street and alongside it were a handful of other big houses like his own, and it was always nice to look at them because they were almost the same as his house but not quite, and other boys lived in them who he played with (if they were friends) or steered clear of (if they were trouble). The new house, however, stood all on its own in an empty, desolate place and there were no other houses anywhere to be seen, which meant there would be no other families around and no other boys to play with, neither friends nor trouble.

The house in Berlin was enormous, and even though he'd lived there for nine years he was still able to find nooks and crannies that he hadn't fully finished exploring yet. There were even whole rooms-such as Father's office, which was Out Of Bounds At All Times And No Exceptions-that he had barely been inside. However, the new house had only three floors: a top floor where all three bedrooms were and only one bathroom, a ground floor with a kitchen, a dining room and a new office for Father (which, he presumed, had the same restrictions as the old one), and a basement where the servants slept.

All around the house in Berlin were other streets of large houses, and when you walked towards the centre of town there were always people strolling along and stopping to chat to each other or rushing around and saying they had no time to stop, not today, not when they had a hundred and one things to do. There were shops with bright store fronts, and fruit and vegetable stalls with big trays piled high with cabbages, carrots, cauliflowers and corn. Some were overspilling with leeks and mushrooms, turnips and sprouts; others with lettuce and green beans, courgettes and parsnips. Sometimes he liked to stand in front of these stalls and close his eyes and breathe in their aromas, feeling his head grow dizzy with the mixed scents of sweetness and life. But there were no other streets around the new house, no one strolling along or rushing around, and definitely no shops or fruit and vegetable stalls. When he closed his eyes, everything around him*just felt empty and cold, as if he was in the loneliest place in the world. The middle of nowhere.

In Berlin there had been tables set out on the street, and sometimes when he walked home from school with Karl, Daniel and Martin there would be men and women sitting at them, drinking frothy drinks and laughing loudly; the people who sat at these tab

les must be very funny people, he always thought, because it didn't matter what they said, somebody always laughed. But there was something about the new house that made Bruno think that no one ever laughed there; that there was nothing to laugh at and nothing to be happy about.

'I think this was a bad idea,' said Bruno a few hours after they arrived, while Maria was unpacking his suitcases upstairs. (Maria wasn't the only maid at the new house either: there were three others who were quite skinny and only ever spoke to each other in whispering voices. There was an old man too who, he was told, was there to prepare the vegetables every day and wait on them at the dinner table, and who looked very unhappy but also a little angry.)

'We don't have the luxury of thinking,' said Mother, opening a box that contained the set of sixty-four glasses that Grandfather and Grandmother had given her when she married Father. 'Some people make all the decisions for us.'

Bruno didn't know what she meant by that so he pretended that she'd never said it at all. 'I think this was a bad idea,' he repeated. 'I think the best thing to do would be to forget all about this and just go back home. We can chalk it up to experience,' he added, a phrase he had learned recently and was determined to use as often as possible.

Mother smiled and put the glasses down carefully on the table. 'I have another phrase for you,' she said. 'It's that we have to make the best of a bad situation.'

'Well, I don't know that we do,' said Bruno. I think you should just tell Father that you've changed your mind and, well, if we have to stay here for the rest of the day and have dinner here this evening and sleep here tonight because we're all tired, then that's all right, but we should probably get up early in the morning if we're to make it back to Berlin by tea-time tomorrow.'

Beneath the Earth

Beneath the Earth The Boy in the Striped Pajamas

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas Next of Kin

Next of Kin The House of Special Purpose

The House of Special Purpose A Ladder to the Sky

A Ladder to the Sky A History of Loneliness

A History of Loneliness The Heart's Invisible Furies

The Heart's Invisible Furies The Boy at the Top of the Mountain

The Boy at the Top of the Mountain Stay Where You Are and Then Leave

Stay Where You Are and Then Leave Crippen: A Novel of Murder

Crippen: A Novel of Murder The Absolutist

The Absolutist Mutiny: A Novel of the Bounty

Mutiny: A Novel of the Bounty A Traveler at the Gates of Wisdom

A Traveler at the Gates of Wisdom The Congress of Rough Riders

The Congress of Rough Riders The Thief of Time

The Thief of Time The Boy in the Striped Pajamas (Deluxe Illustrated Edition)

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas (Deluxe Illustrated Edition) The Terrible Thing That Happened to Barnaby Brocket

The Terrible Thing That Happened to Barnaby Brocket The Boy In The Striped Pyjamas

The Boy In The Striped Pyjamas Crippen

Crippen